12 Ways to Support and Celebrate Minnesota's Native American Communities

Minnesotans owe many of the things we love about our state — from its rich multicultural makeup to its beautiful, well-preserved nature areas — to the Native American communities that have long resided here. That’s not hyperbole; these Indigenous peoples have stewarded this place for millennia.

Today, 11 federally recognized Tribes call the Land of 10,000 Lakes home. Here are 12 ways to support and celebrate these wholly unique groups, including participating in local powwows, checking out contemporary art shows and comedians, and shopping at stellar book, food and handicraft stores.

-

1. Honor the ancestral homelands you're on

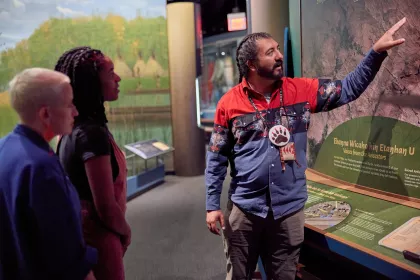

A couple takes a tour through Hocokata Ti cultural center / Credit: Paul Vincent

A couple takes a tour through Hocokata Ti cultural center / Credit: Paul VincentLong before Minnesota became a state, the Dakota and Anishinaabe people were living in harmony with the world around them. This is also a culturally important place for the Ho-Chunk, Cheyenne, Oto, Iowa, and the Sac and Fox Tribes. When Europeans arrived, these communities faced horrifically oppressive policies and conditions, including displacement, dispossession, and disenfranchisement.

The enduring legacy of American colonialism can still be felt in Tribal communities, which face ongoing discrimination, notable health inequities, and high rates of poverty, addiction, and suicide. Minnesota’s complicated, challenging history with its original peoples is well-documented through cultural institutions such as Hoċokata Ṫi and the Minnesota Historical Society.

-

2. Expand your knowledge in nature

Dakota Sacred Hoop Walk at Minnesota Landscape Arboretum

Dakota Sacred Hoop Walk at Minnesota Landscape ArboretumPlace-based learning is a wonderful way to engage with history while also communing with nature — an important practice according to an Indigenous worldview. The Minnesota Landscape Arboretum’s Dakota Sacred Hoop Walk, for instance, is an augmented reality exhibition made by Spirit Lake Dakota artist Marlena Myles that combines digital imagery and audio to educate guests about Dakota culture

Meanwhile, the Minnesota Humanities Center periodically hosts immersive Learning from Place: Bdote experiences that offer participants a deeper understanding of places like Fort Snelling State Park, Indian Mounds Regional Park, and Oheyawahi/Pilot Knob.

-

3. Learn an Indigenous language

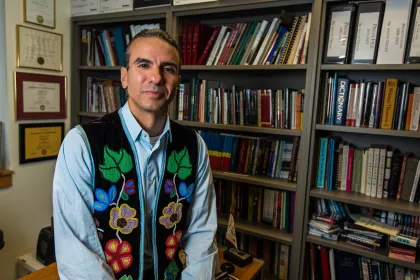

Bemidji State University professor Anton Treuer

Bemidji State University professor Anton TreuerWhile you’re out walking the walk, why not also talk the talk — quite literally? Language is a beautiful and crucial component of culture not only in foreign countries but also for sovereign Tribal nations right here in the United States. Learning any language takes work, but Minnesota-based resources like the Culture Language Arts Network and the Ojibwe Rosetta Stone Project can help.

There are also more casual ways to embrace Indigenous languages, including playing Nashke Native Games, downloading the Dakhóta iápi Okhódakičhiye language app, or watching Ojibwe author/educator Anton Treuer’s captivating videos.

-

4. Visit culturally significant sites

A couple hikers at Pipestone National Monument / Paul Vincent

A couple hikers at Pipestone National Monument / Paul VincentSpeaking of notable places, Minnesota is dotted with several Indigenous areas worth exploring, including Grand Portage National Monument, Jeffers Petroglyphs, Pipestone National Monument, Mankato’s Reconciliation Park, and the Mille Lacs Indian Museum and Trading Post. While they all add to the cultural context and richness of our state, each holds space for a unique and important story — a reminder that Native cultures (and experiences) are not a monolith.

-

5. Explore Minneapolis' cultural corridor

Woman looking at an exhibit at All My Relations Gallery / All My Relations Gallery

Woman looking at an exhibit at All My Relations Gallery / All My Relations GalleryThe Twin Cities boasts a thriving Native scene, as exemplified by Minneapolis’s Franklin Avenue East District. Spanning several blocks, the area earned its moniker thanks to its plentiful Indigenous-created public art and Native-led businesses and organizations, including All My Relations Arts Gallery, Pow Wow Grounds coffee shop, and the recently renovated Minneapolis American Indian Center (MAIC). All are welcome in these places, though MAIC does have some exclusive programming intended to support the local Indigenous community.

-

6. Savor traditional and contemporary flavors

Bison New York strip with sweet potato hash, charred tomato hollandaise and grilled dandelion greens at Owamni / Credit: Dana Noelle Thompson

Bison New York strip with sweet potato hash, charred tomato hollandaise and grilled dandelion greens at Owamni / Credit: Dana Noelle ThompsonMuch to foodies’ delight, Minnesota is home to some of the top Indigenous-led restaurants in the country. Just ask the James Beard Foundation, which named Owamni America's Best New Restaurant in 2022. Acclaimed Oglala Lakota chef Sean Sherman also leads the Indigenous Food Lab Market, housed within the Midtown Global Market. At both establishments, Sherman serves food made without Eurocentric ingredients—like beef, pork, chicken, dairy, wheat flour, and cane sugar—instead highlighting foods sourced from Indigenous purveyors, such as tea from Duluth’s own Anahata Herbals.

There’s even more to savor from the Trickster Tacos food truck, Makwa Coffee, and Gatherings Cafe at MAIC. Local ingredients like walleye, wild rice, maple syrup, wild berries, morel mushrooms, and fiddleheads feature prominently on menus that offer creative takes on traditional dishes. Home cooks can also buy these ingredients to craft nutritious, delicious meals in their own kitchens.

-

7. Soak in an illuminating show

Cara Romero's "TV Indians" from the Minneapolis Institute of Art show "In Our Hands"

Cara Romero's "TV Indians" from the Minneapolis Institute of Art show "In Our Hands"Why not make it dinner and a show? From performing arts to visual arts, there’s no shortage of evocative Indigenous entertainment on stages and in galleries across Minnesota. Native storytellers statewide offer honest, authentic depictions of Tribal communities and issues at inclusive venues like All My Relations, New Native Theatre, Two Rivers Gallery, Tweed Museum of Art, and major institutions such as the Guthrie Theater and Minneapolis Institute of Art.

-

8. Lose yourself in literature

Birchbark Books & Native Arts

Birchbark Books & Native ArtsMinnesota also boasts major bragging rights for its many renowned Indigenous authors, including Louise Erdrich (Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa), the matriarch behind the popular Birchbark Books in Minneapolis. She is in good company alongside writers like Tashia Hart (Red Lake Nation), Mona Susan Power (Standing Rock Sioux), Marcie Rendon (White Earth Nation), Anton Treuer, and David Treuer (Leech Lake Ojibwe), among other rising stars who showcase the depth and richness of Indigenous life through the power of the pen.

-

9. Participate in a powwow

The Grand Portage Annual Powwow and Rendezvous / Credit: Stephan Hoglund

The Grand Portage Annual Powwow and Rendezvous / Credit: Stephan HoglundAlthough some private events are reserved for their respective Tribal nations, Indigenous celebrations are often open to the public. Knowledge keepers are eager to share their Tribe’s unique cultural practices at powwows, festivals, and other gatherings. Many events take place around Indigenous Peoples’ Day in October and American Indian Month in May, but there are festivities year-round.

Word to the wise: Many event organizers provide etiquette tips online to help visitors appreciate traditions respectfully without appropriation or disrespect. When in doubt, ask for permission rather than forgiveness.

-

10. Laugh out loud

Dallas Goldtooth in "Reservation Dogs"

Dallas Goldtooth in "Reservation Dogs"Humor is medicine for Indigenous peoples — medicine meant to be shared. Jokes often touch on difficult parts of Native life, but like all comedy, they bring levity and understanding.

Minnesota is home to a pretty funny bunch, including Trish Cook (Red Lake Nation), Rob “Rez Reporter” Fairbanks (Leech Lake Ojibwe), and Dallas Goldtooth (Bdewakantunwan Dakota/Dińe) of the 1491s and "Reservation Dogs" fame. You can also catch touring stand-up comedians like Tatanka Means (Navajo/Omaha/Oglala Lakota) at local casinos and venues. Non-Native audiences are welcome — and encouraged — to enjoy Native-focused humor.

-

11. Shop Indigenous

Woodland Crafts Gift Shop at Minneapolis American Indian Center / Credit: Lisa A Lardy

Woodland Crafts Gift Shop at Minneapolis American Indian Center / Credit: Lisa A LardyIf you want to make a meaningful impact, supporting Native artisans and entrepreneurs is a powerful way to uplift Tribal nations, which continue to face economic hardships and inequities. Do some good while shopping at popular local spots like Birchbark Books, the Indigenous Food Lab Market, Indigenous First, Northland Visions, and the Woodland Crafts Gift Shop. Most offer online shopping as well.

-

12. Support a Native-led nonprofit

MIGIZI's annual sugarbush trip

MIGIZI's annual sugarbush tripTime, money, energy, platform — all of these resources amplify the efforts of Native-led nonprofits, which receive just 0.4 percent of philanthropic dollars from large U.S. foundations, per recent Candid research . That statistic alone should be incentive enough, but equally motivating is the joy that comes with altruistic action supporting marginalized groups. It’s important to ensure that the organization or initiative you’re championing is indeed Indigenous-led and Indigenous-serving, though.

Thankfully, Minnesota is home to plenty of Native-oriented nonprofits with specific focus areas, from food sovereignty ( Dream of Wild Health) to housing insecurity ( AICHO) to youth cultural development ( MIGIZI), to highlight just a few. You can start by finding a cause that resonates with you, taking time to learn about your local community's most pressing needs, or searching the Minnesota Council of Nonprofits.

Read about many of the different cultures that call Minnesota home.